At nearly 100 years old, dates and details don’t come as easily to Cal State LA alumnus Sigmund Burke. But certain memories are forever emblazoned in the mind of the Holocaust survivor.

Nazi guards ripping his family away from one another’s arms at the gates of the

Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. The last time he ever saw his mother, sister and nephew.

The deterioration of his body into skin and bones. The bites covering his waist from lice that infested the camp barracks and the little clothing he and other prisoners were given.

His inmate number. “82830,” he recites quickly from memory. The digits add up to 21, a lucky number, he says and smiles. “That’s when I knew I was going to make it.”

This year marks the 76th anniversary of Burke’s escape and the end of the Holocaust, during which the Nazis and their collaborators murdered 6 million Jewish men, women and children, as well as millions of others, from 1941 to 1945.

Burke, now 97 years old, is one of a dwindling number of Holocaust survivors living today. Some organizations estimate there are approximately 400,000 left, and all are elderly. With fewer around to recount their experiences firsthand, many fear awareness of the atrocities will fade.

A nationwide survey in 2020 found that many millennials and members of Generation Z lack knowledge of the basic facts of the Holocaust—48% of respondents could not name a single one of the more than 40,000 concentration camps and ghettos established during World War II, and 56% had no knowledge of Auschwitz.

“The results are both shocking and saddening and they underscore why we must act now while Holocaust survivors are still with us to voice their stories,” said Gideon Taylor, president of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany that commissioned the study, after the findings were released.

Burke is worried, too.

“They need to know so it will never happen again,” Burke said during an interview with California State University, Los Angeles Magazine. “I am afraid that people will eventually forget and won’t believe it ever happened.”

By telling his story time and again over nearly eight decades, Burke has been able to preserve his memories—memories that not only constitute his remarkable life but carry with them the weight of history.

With each telling, he wards off the near inevitable reality that memories fade with time, and pushes back against the tendency for society to turn away from the painful, shameful and difficult moments in history.

He’s told his story. And he’s told it again. And again.

To his grandchildren and their classmates at school. To his now adult children, Robin Berkovitz, Bob Burke and David Burke, throughout their lives. To his fellow residents in the Beverly Hills assisted-living apartment complex he calls home. To nonprofit organizations like the USC Shoah Foundation and the Anti-Defamation League that are dedicated to preserving the testimony of Holocaust survivors.

“They need to know so it will never happen again. I am afraid that people will eventually forget and won’t believe it ever happened.”

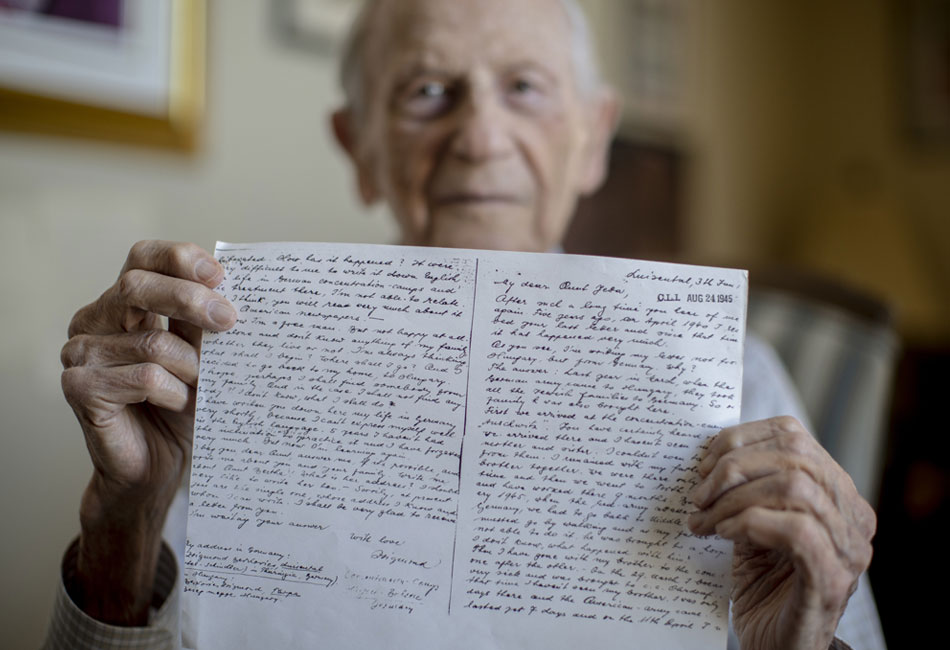

Hearing has gotten more difficult—he wears hearing aids in each ear. And he relies on a collection of artifacts: typed pages, photo albums and records he’s written and carefully compiled over the last three-quarters of a century.

Burke’s wispy white hair is pushed back, styled as it was when he was a young man. A slight Hungarian accent comes through as he speaks.

With black-rimmed reading glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, Burke begins to tell his story, aided by his collection. It helps him tell the story of a young Jewish boy from Tarpa, Hungary, who turned into a 21-year-old survivor of the worst of humanity, who came to America, and then grew into the 97-year-old man he is today.

Burke picks up one of the typewritten pages stacked on his wooden kitchen table, and begins to read: “After so many years, many of the day-to-day events and details about the events have faded in my memory, but a number of episodes—indelibly etched in my mind—still remain clear.

“Some of these episodes recall those occurrences that left the deepest impression on me, either because of the personal trauma associated with them or because they represented human behavior at its best or worst, that only a concentration camp environment can bring out in a human being.

“The others can be classified as those individual miracles which contributed to my survival, those that made the difference between life and death.”

He pauses, and looks up with a confident smile.

“That was pretty good, huh?”

Photo: Sigmund Burke holds a handwritten letter he wrote to family in the United States in August 1945, one of the many artifacts he has saved and collected to help tell his story. (Credit: J. Emilio Flores/Cal State LA)

Burke, who was born Sigmund Berkovics, can recall when he started noticing signs of the rise of antisemitism as an 8- or 9-year-old in Tarpa, a small village in northeast Hungary. That was when he first heard the slur “dirty Jew” hurled. Then the town prohibited Jewish youth from attending school, so Burke’s high school days ended. His parents lost their tavern and grocery business as Jews increasingly experienced rising hatred and were stripped of their rights.

Then came a knock on the door at 3 a.m. on April 15, 1944. A neighbor with an official edict: The Berkovics family—Sigmund, his father, mother, brother, sister and her son—were to report to the local schoolhouse by the next afternoon with only the belongings they could carry.

The Berkovics family and several thousand other Jewish people from surrounding areas were deported to a nearby ghetto, the site of an old brick factory. They were kept there for about a month or so, a 70-year-old Burke recalled in a 1994 oral history interview recorded by the Anti-Defamation League of Orange County. They were then packed into cattle cars and taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest and most infamous Nazi concentration camp during World War II.

The men were ripped away from the women and children—Burke, his father and brother forever separated from his mother, sister and nephew. A man nearby said to the father and sons: Do you smell this smell? This smoke? Those are your relatives. “We still didn’t want to believe it,” Burke said in the 1994 interview.

Over the next year, Burke, his father and brother were transported to and imprisoned in several Nazi concentration camps, where they were forced to do grueling work like building barracks and digging tunnels in mountainsides that would eventually become the site of German V-2 rocket factories.

But with the carpentry skills Burke had picked up as a young boy, he was able to avoid some of the most backbreaking work. He tries to remember the projects, pausing as he seemingly searches for the specific memory. “You know, I don’t remember things anymore,” he says.

His daughter, Robin, knows his story well. She prompts him: “Didn’t you make wooden suitcases, Dad?”

Yes, that’s it, he remembers. He’d make wooden suitcases for the guards in exchange for an extra plate of potatoes or a piece of bread that he would share with his father and brother. Burke’s father would use the food as part of a traditional Jewish Kiddush blessing on Friday evenings.

Photo: Sigmund Burke and his daughter, Robin Berkovitz, share a moment. (Credit: J. Emilio Flores/Cal State LA)

“All this time, even though conditions were almost hopeless, my father had this optimistic view, that we all would survive,” Burke said. “He would always ask me what plans I have to continue my education when we go home.”

Over time, Burke was separated from his father and brother and found himself on what felt sure to be a death march in the spring of 1945. Dehydrated and starving, Burke marched alongside fellow prisoners in lines of five, a detail he remembers to this day.

“I knew I couldn’t last too much longer under those conditions,” he says. “I decided I would escape at the first opportunity I had.”

The men marched in darkness but for the bombs, burning tanks and cannons exploding all around. German soldiers and dogs surrounded them as they walked ahead on the road that ran through open fields. Burke made sure he was on the edge of the group, and ran his hands along a bordering wooden fence.

And then, he felt it. An open gate.

“This is it,” he remembers. “I am either going to live or I am going to die.”

He slipped away from the group into the darkness and quietly ran for his life.

After an eight-day journey through the cold German spring, hiding in a barn and an old model airplane factory with only coat lining wrapped around his feet, Burke lived. He reached the town of Luisenthal, Germany, where he found U.S. troops and was liberated.

The soldiers took him to their headquarters in a nearby hotel, where they gave him food and helped start him on his road to recovery. Burke remembers looking at his reflection.

“I hardly recognize myself,” he said to an interviewer from the USC Shoah Foundation as part of an oral history project in 2019, reading from his typed testimony from years before. “I am skin and bones, holes around my waist eaten out with lice. I looked like all those bodies I have seen and handled [in the camps], only I am alive.

“I realize I am liberated and a free man. The exhilaration I feel is indescribable. I ask the guard to bring me a pencil and paper, and immediately I begin to write my story.”

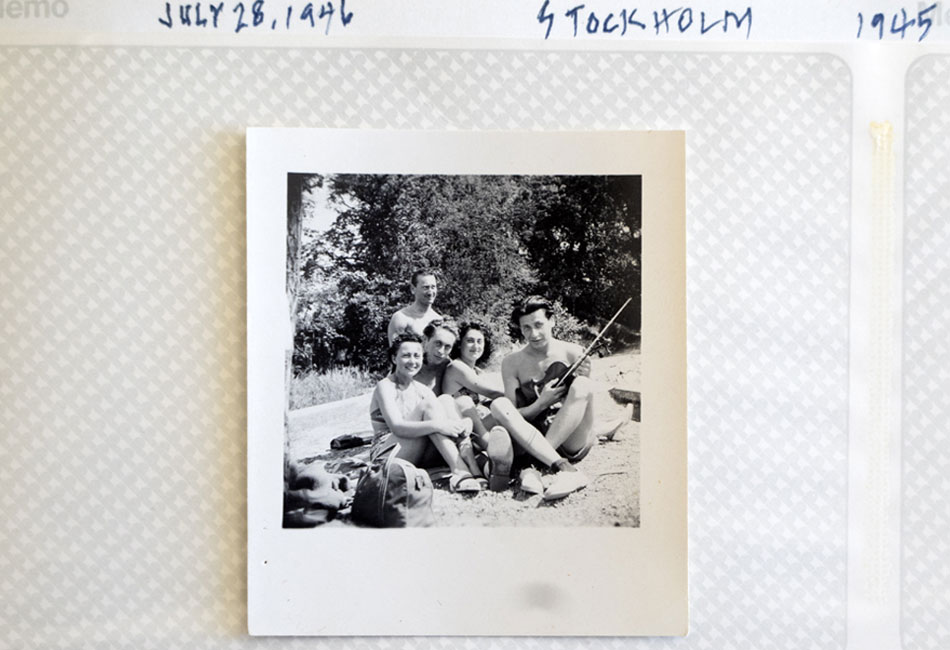

Burke made his way to Sweden later in 1945, where many survivors gathered after the war. He would eventually reunite with his father and brother, who both also managed to survive. It was in Sweden where he met his wife, Edith, another Holocaust survivor.

They’d both make their way to the United States—first Burke to California by way of Cleveland with the help of distant relatives, and then Edith to New York, before the couple reunited, married and settled in Los Angeles.

When Sigmund became a U.S. citizen, he changed his last name from Berkovics to Burke. (His daughter changed her last name to Berkovitz to pay homage to her family.)

Photo: A photograph of Sigmund Burke (far right) on a trip to Stockholm, Sweden, in July 1946 with friends, including his future wife, Edith, (center).

In Los Angeles, he started out as a layout draftsman for the American Monorail Company and then a structural designer in 1952 for Fluor, a global engineering and construction company.

During the day, Burke worked at project sites, and at night he attended classes at Cal State LA, then known as Los Angeles State College. “If you ask me what courses I took, I couldn’t tell you,” he says with a laugh. But he enjoyed the work, though it was difficult balancing his job, family and school.

With a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering under his belt by 1963 from what is now Cal State LA’s College of Engineering, Computer Science, and Technology, Burke worked his way up the ladder at Fluor, eventually overseeing the company’s Southern California Structural Engineering Department. Before his retirement in 1986, he worked on pipeline, refinery expansion and natural gas plant projects across the world, including in Indonesia, Australia, Spain and the U.S.

In 2019, at age 95, Burke stepped back onto Cal State LA’s campus for an Alumni Association reunion, over half a century after he earned his degree.

Much had changed on campus and in the world since Burke’s years in college at Cal State LA. He noticed the newer and bigger buildings. More students, classes and majors.

During his time in school, the Soviet Union landed a probe on the moon, the Dodgers moved from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, and President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. The 1950s and 1960s saw the birth of the modern civil rights movement, and yet today the nation continues to grapple with its history of racial injustices.

A quote graces an inside page of the Los Angeles State College yearbook from 1963, the year Burke graduated: “Memories are created to be left behind; however, let the past have meaning and teach us that we can make firm imprints on the path of the future.”

“Memories are created to be left behind; however, let the past have meaning and teach us that we can make firm imprints on the path of the future.”

– Los Angeles State College yearbook, 1963

Burke’s memories of his experience during the Holocaust are painful—and for some Holocaust survivors, like Burke’s wife, Edith, who died in 1999, they were too painful to revisit or recount. But for Burke, telling his story has been cathartic, a way to find meaning in his experience, and most importantly, he believes, necessary.

During the February 2020 interview, Burke sat in his apartment inside an assisted-living complex on a tree-lined street in Beverly Hills and gazed outside his window.

“I am worried about the world today,” he said. He worried about the rise of far-right extremism in the U.S. and across Europe. He worried about history repeating itself.

His books lay stacked on a nearby table—Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician and Leo Rosten’s Carnival of Wit: From Aristotle to Groucho Marx. Below an engineering coffee table book: Bob Woodward’s Fear: Trump in the White House and It’s Better Than It Looks: Reasons for Optimism in an Age of Fear.

His books lay stacked on a nearby table—Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician and Leo Rosten’s Carnival of Wit: From Aristotle to Groucho Marx. Below an engineering coffee table book: Bob Woodward’s Fear: Trump in the White House and It’s Better Than It Looks: Reasons for Optimism in an Age of Fear.

When Burke reflects on his nearly full century of living, what stands out the most is the career and family he was able to build with the love of his life, Edith, and the children they raised into successful adults who have found ways to give back to the world—Robin as a public defender, Bob as a now retired project manager and David as a psychologist.

“I am most proud of the things that I accomplished in spite of everything,” he said.

As the dates and details begin to leave him, he worries that the world will forget. But his story won’t be forgotten. The 21-year-old Holocaust survivor who put pencil to paper in a hotel room in a village in Germany 76 years ago made sure of it.

As Robin helped Burke up to his walker and out of his room, she asked her father: “What was your number again, Dad?”

“82830,” he said, without hesitation.

# # #

California State University, Los Angeles is the premier comprehensive public university in the heart of Los Angeles. Cal State LA is ranked number one in the United States for the upward mobility of its students. Cal State LA is dedicated to engagement, service, and the public good, offering nationally recognized programs in science, the arts, business, criminal justice, engineering, nursing, education, and the humanities. Founded in 1947, the University serves more than 26,000 students and has more than 250,000 distinguished alumni.

Cal State LA is home to the critically-acclaimed Luckman Fine Arts Complex, Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs, Hertzberg-Davis Forensic Science Center, Hydrogen Research and Fueling Facility, Billie Jean King Sports Complex and the TV, Film and Media Center. For more information, visit www.CalStateLA.edu.